Spirits - Boxed & Bottled.

Did you have a particular favourite book when you were younger? Do you recall a special story that, once found, you ended up reading over and over, returning to its pages so many times you could almost recite passages from it almost word for word?

For me, it was around age 10 or 11, when I came across a copy of The Ghost of Thomas Kempe, by Penelope Lively in the school library. First published by Heinemann in 1973 with illustrations by Anthony Maitland. It became something of an instant classic when released (indeed it won the Carnegie Medal) and instantly became a firm favourite of mine. In fact I’m glad to see it has kept in print right up till now, with the most recent edition coming out in 2018.

Being a child with a healthy appreciation for all things gothic and gloomy, this was the very first story I recall that treated a ghost in something of a way that felt real. Set in a very early 1970s Oxfordshire town, The protagonist James and his family move into a cottage, that soon begins to exhibit classic poltergeist-like activity, and James discovers through the course of the tale that his is being ‘recruited’ as the new assistant to a 17th-century ‘cunning man’ or sorcerer who lived there 300 years previously.

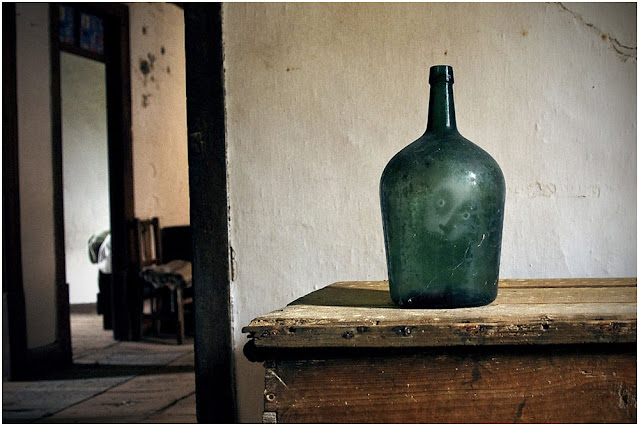

The opening passage of the story, set before the family arrive in their new home, introduces us to an upstairs room (which will soon be James’s bedroom) that is being refurbished by two local builders, and in removing a rotten wooden window sill, they disturb and break a small glass bottle hidden within the wall. We later find out that this vessel contained the trapped spirit of Thomas Kempe. This idea of a spirit or soul being imprisoned in a bottle like a genie in the lamp fascinated my young mind.

|

| The builders unwittingly, break the bottle releasing the spirit of Thomas Kempe. One of the fantastic illustrations dotted throughout the book by Anthony Maitland. |

So it’s not surprising that years later while reading up on Lincolnshire Folklore I came across the following account from the Tupholme (East Lindsey) area which immediately brought memories of this book flooding back.

"A woman who died from neglect, and whose husband married the woman who ought to have attended to her, haunted the cottage until her spirit was laid in a box and buried in the cottage by a clergyman; but when the man died in 1840 and the cottage was taken down, the workmen broke open the box in which the woman’s spirit had been laid for thirty years, but it then burst forth, with such a sound as if all the trees in the neighbouring wood were falling, so that the workmen ran away in terror." [1]

In The Ghost of Thomas Kempe, James, the boy at the centre of the story is dismayed to find his practical and modern minded parents flat refuse even to discuss the supernatural with him. And the village Vicar is more concerned with recruiting James to choir activities than addressing any supernatural problems he may have. In the end, James is directed to Bert Ellison, a local builder and something of an odd-job occult practitioner. Bert attempts to lay the rogue spirit, by trapping him again through a ritual that uses seven candles and a bottle that can stoppered with a cork.

|

| Bert Ellison attempts to lure the ghost back into a bottle. |

So you can imagine maybe a similar endeavour was undertaken by the clergyman at Tupholme to entice into, and imprison the spirit inside the box, which was then hidden within the fabric of the cottage, only to be found later during the demolition. Bottles and boxes were however not the only options available to anyone looking to lay a restless spirit. As can be seen in another account from Lincolnshire.

The Pilford Bridge Spirit

Pilford Bridge, a small arch that carries the road between Normanby-by-Spital and Middle Rasen over the River Ancholm, was once reputed to be haunted by a vicious entity, which took malicious pleasure in pushing travellers over the edge of the bridge into the water below.

| ||

| Pilford Bridge, crossing the River Ancholme. © Jonathan Thacker - geograph.org.uk/p/5167078 |

"Life I want, and Life I shall have!"

Presumably the pot is still there, submerged in the mud at the bottom of the stream, with the cold waters of the River Ancholme running over it. But the lady who told this tale to folklorist, Ethel Rudkin in the 1930s, [2] had a dire warning for anyone curious or foolhardy enough to go looking to disturb it.

“But if they were ter raise that pot even now, the spirit ‘ud cum out agen’ an be as bad as iver”

I think that’s a warning which we should take care to follow.

---------------------------

Comments

Post a Comment